The Charlevoix Coast and the St-Lawrence Estuary

Marine mammals

Seals

Two species of seals frequent the Saint Lawrence Estuary near Saint-Irénée: the harbor seal and the gray seal. These marine mammals regularly haul out on rocks exposed at low tide, where they can be observed from the shore. Their presence reflects the richness of the ecosystem and the health of the marine environment.

Harbor seal

- Length: 1.5 to 1.8 meters

- Weight: 80 to 100 kg

- Lifespan: ~36 years

- Birthing season: mid-May to mid-June

- Dive duration: 3–7 minutes (max 20 minutes)

- Dive depth: up to 100 meters

Gray seal

- Length: 2 to 2.5 meters

- Weight: 200 to 350 kg

- Lifespan: ~40 years

- Birthing season: December to February

- Dive duration: 5–10 minutes (max 30 minutes)

- Dive depth: up to 200 meters

Cetaceans

Two cetacean species regularly inhabit the Saint Lawrence Estuary: the beluga, present year-round, and the harbor porpoise, most active during the summer. Observing them from the shore or by kayak adds a fascinating dimension to wildlife watching.

Beluga

- Length: 3–5 meters

- Weight: 500–1,500 kg

- Lifespan: 50–70 years

- Birthing season: June to September (one calf every three years)

- Dive duration: 10–15 minutes

- Dive depth: typically 20–50 meters (max 300–400 meters)

Harbor porpoise

- Length: 1.5–2 meters

- Weight: 45–65 kg

- Lifespan: 15–20 years

- Birthing season: June to July (one calf per year)

- Dive duration: 2–6 minutes

- Dive depth: typically 50–100 meters (max 200 meters)

Birds of the estuary

The shores of the Saint Lawrence host a wide variety of seabirds and waterbirds, many easily observed from the shore or by kayak. Notable species include the common loon, great cormorant, great blue heron, and two small alcid birds: the thick-billed murre and the razorbill. These species highlight the biological richness of the river and its coastal zones.

Common loon

- Length: 66–91 cm

- Wingspan: 127–147 cm

- Weight: 3–7 kg

- Lifespan: 20–30 years

- Presence: May to September

- Dive duration: 1–3 minutes (max 5)

- Dive depth: 5–20 meters

Great cormorant

- Length: 80–90 cm

- Wingspan: 120–160 cm

- Weight: 2–2.5 kg

- Lifespan: 15–20 years

- Presence: April to October

- Dive duration: 30 sec–1 min (max 2)

- Dive depth: 5–20 meters (sometimes up to 30)

Great blue heron

- Length: 97–137 cm

- Wingspan: 167–201 cm

- Weight: 2–2.5 kg

- Lifespan: ~15 years

- Presence: April to October

- Diet: fish, frogs, insects, small mammals

Similarity and distinction : Thick-billed murre and razorbill

Offshore, two small alcid birds draw attention: the thick-billed murre and the razorbill. They are similar and not always easy to distinguish.

Thick-billed Murre

- Length: 39–43 cm

- Wingspan: 60–69 cm

- Weight: 500–800 g

- Special trait: rapid wingbeats

- Dive depth: up to 60 meters

Razorbill

- Length: 38–46 cm

- Wingspan: 64–73 cm

- Weight: 900–1,100 g

- Special trait: fast flight

Coastal algae and plants

The shores and beaches of Saint-Irénée host a variety of marine and coastal vegetation, essential to ecosystem balance. They provide food and shelter for many animals, protect the coastline from erosion, and contribute to local biodiversity.

Algae

Fucus bifidus (bladderwrack)

- Role: Provides shelter for small marine animals and protects the coastline

- Appearance: Brown algae in flat ribbons

- Where? Attached to rocks, highly visible at low tide

- Edible? Yes, rich in iodine and minerals, though quite strong in taste

Palmaria palmata (dulse)

- Role: Source of food and shelter for small marine invertebrates

- Appearance: Red algae in flexible strips

- Where? Attached to rocks or larger algae in the lower intertidal zone

- Edible? Yes, very nutritious with an umami flavor, can be eaten raw, dried, or cooked

Sea lettuce (Ulva lactuca)

- Role: Contributes to the balance of the coastal ecosystem and feeds small marine animals

- Appearance: Green algae with thin, bright green leaves

- Where? Attached to rocks, highly visible at low tide

- Edible? Yes, delicate and consumable raw, dried, or in salads

Coastal plants

In addition to algae, the beaches and dunes of the Saint Lawrence host vegetation adapted to extreme coastal conditions. These plants play a crucial role in stabilizing sand, providing shelter and food for wildlife, and sometimes even ending up on our plates.

Sea Rocket (Cakile maritima)

- Role: Stabilizes dunes and provides food and shelter for certain insects and birds

- Appearance: Low-growing plant with fleshy bluish-green leaves, small mauve flowers, and plump clustered fruits

- Where? In beach sand, just above the high-tide line

- **Edible? Yes, with a spicy taste reminiscent of mustard or radish, can be eaten raw in salads or as garnish

Estuary and tides

High tide, Low tide

As soon as you start visiting the banks of the river in Charlevoix, you are struck by its constantly changing nature—its colors, its smells, and especially its tides! Yes, you can observe up to four tides per day (24h). But what exactly is a tide, and how does it work?

It all starts with astronomy! The Sun and the Moon play a crucial role in creating tidal waves. First, the Sun exerts a gravitational pull on all bodies in the Solar System; the mass and distance of objects directly affect the gravitational force between them.

| Mass | Moon = 1% of Earth's mass |

| Sun = 330,000 Earths | |

| Distance | 384 000 km |

| 150 000 000 km |

Par sa grande proximité avec notre planète, la Lune exerce une force similaire. La Terre elle-même possède sa propre force gravitationnelle, ce qui lui permet de rester entière; car toute matière est soumise à la gravité, qu’elle soit à l’état solide, liquide ou gazeux. Mais! Concentrons-nous sur l’eau. Tout dépendant de la position relative entre le Soleil, la Terre et la Lune, les marées connaîtront une hauteur variable, ce qu’on appelle le marnage. Les plus grands marnages sont aussi appelés marées de « hautes-eaux » (spring tides) et ont lieu durant les phases de nouvelle et pleine Lune. Les plus petits marnages sont les marées de mortes-eaux (neap tides), et ont lieu durant les phases lunaires du premier et dernier quartier. Par conséquent, on observe les deux types de marées dans un même mois1. Voici une illustration qui permet de mieux comprendre cette influence.

Due to its proximity to our planet, the Moon exerts a similar force. The Earth itself has its own gravitational force, which keeps it together, as all matter—solid, liquid, or gas—is affected by gravity. Now, let’s focus on water. Depending on the relative positions of the Sun, Earth, and Moon, tides will vary in height—a phenomenon called the tidal range:

- The highest tidal ranges are called spring tides, occurring during new and full moons.

- The smallest tidal ranges are called neap tides, occurring during the first and last lunar quarters.

Thus, both types of tides are observed within the same month1. Here is an illustration that helps to better understand this influence.

Next, think of a tidal wave like a cycle: a rising period (flood tide), a very short period of balance (high tide), followed by a falling period (ebb tide), and another brief period of balance (low tide). This cycle repeats, particularly frequently in the Saint Lawrence Estuary: 3 to 4 times in 24 hours.

Where fresh and salt water meet

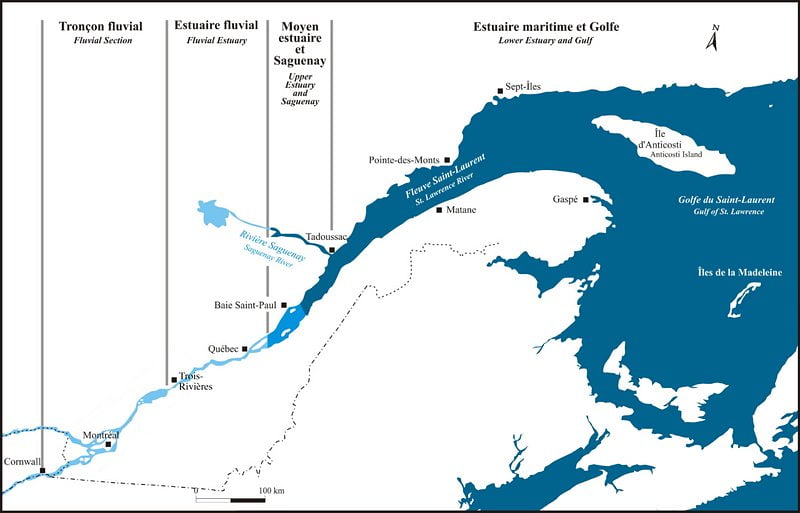

Caution! Tides do not behave the same way along the entire Saint Lawrence River. They also help define four distinct sections:

- Fluvial Section: Between Cornwall and Lac Saint-Pierre, where the water is fresh and tides are absent.

- River Estuary: From the Lac Saint-Pierre outlet to the eastern tip of Île d’Orléans, where water is mostly fresh but tidal effects can be measured.

- Middle Estuary: From the eastern tip of Île d’Orléans to Tadoussac, where the river widens and freshwater from the Great Lakes mixes with salty water from the Gulf; this is called brackish water. Want to test it? Taste the water in Baie-Saint-Paul, then in Saint-Siméon—you’ll likely be surprised! The Charlevoix coasts are entirely within this middle estuary. This section is also where the habitat of several marine mammals, including belugas, begins. Tides here are significant (up to 6 meters tidal range) and navigating this section is challenging due to rapidly changing bathymetry.

- Maritime Estuary and Gulf: From Tadoussac to Pointe-des-Monts, where water is definitely saltier and colder. The riverbed widens and deepens, allowing observation of a wide variety of marine mammals, from harbor porpoises to blue whales, Greenland seals, and white-sided dolphins.

A river for experienced navigators

Did you know that all vessels longer than 35 meters operating in the Saint Lawrence must be piloted by an expert? This is the role of the Corporation of Pilots of the Saint Lawrence, which trains specialists for each river section to ensure safe and efficient navigation. In the middle estuary, vessels must follow the Laurentian Channel, located between Isle-aux-Coudres and Saint-Joseph-de-la-Rive. Navigating south of the island is nearly impossible due to shallow waters and numerous shoals.